Lost in Transmission

Why Oral Tradition Produces Myth, Not Certainty

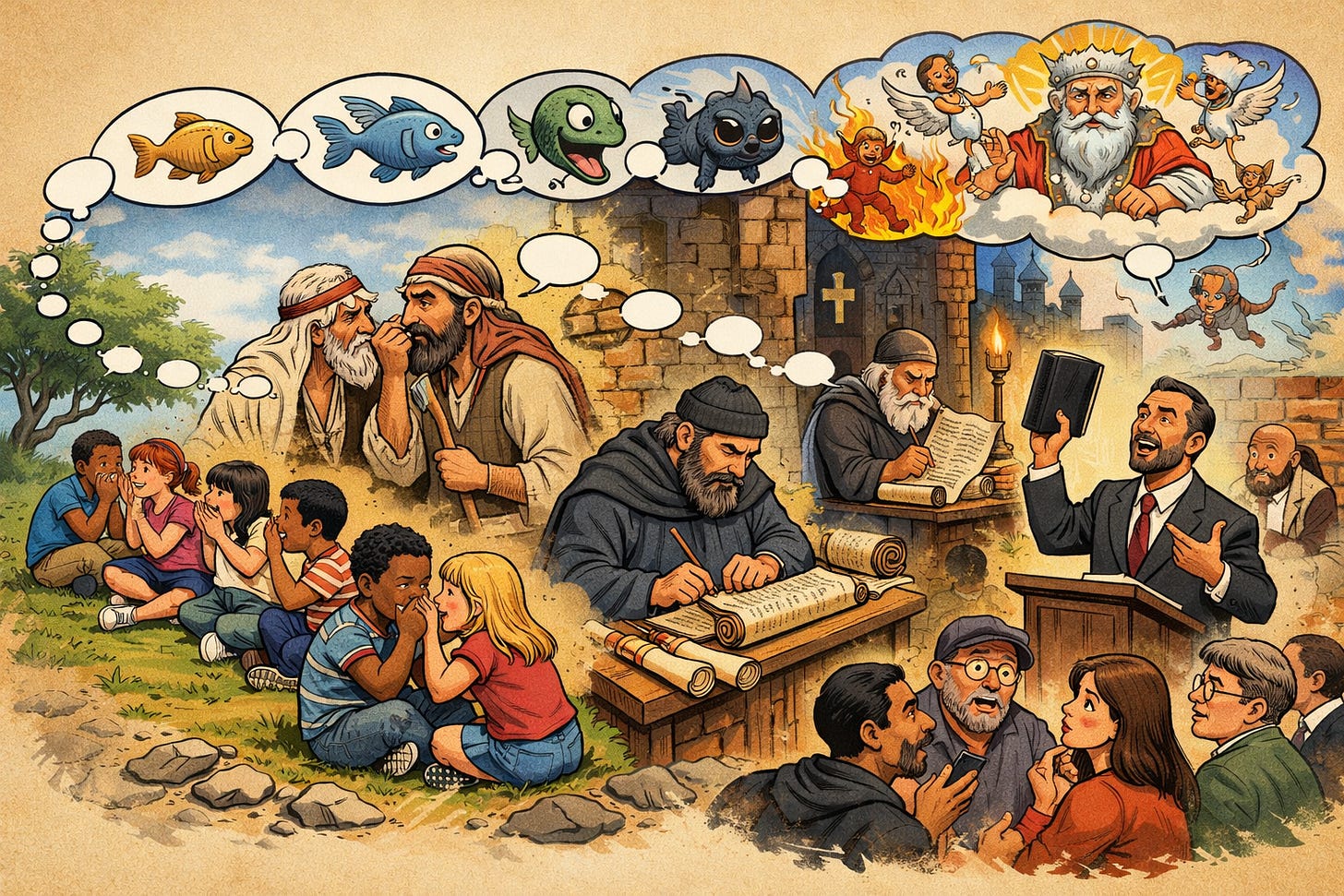

Every child who has ever sat cross-legged on a classroom floor knows the game of Telephone. A sentence is whispered from one ear to the next, passed hand-to-mouth around a circle of increasingly mischievous intermediaries. By the time it reaches the final participant, the message bears only a passing resemblance to its origin. The exercise is not merely a diversion; it is a demonstration. It shows—viscerally, memorably—that human transmission is fallible, distortion-prone, and irresistibly shaped by memory, bias, misunderstanding, and invention.

And yet, with a straight face and a solemn hymn, churches ask us to believe that the Bible—the most theologically loaded text ever produced—somehow escaped every rule the Telephone game so efficiently exposes. Not just mostly intact. Not broadly accurate. But perfect. Inerrant. The literal word of God. This is not faith; it is an insult to reason dressed up as reverence.

The central absurdity lies not merely in the claim of divine inspiration, but in the mechanism of delivery. For centuries, the stories that would become the Bible were not written at all. They were spoken. Repeated. Performed. Reworked. Passed from tribe to tribe, from elder to child, from priest to congregation. Oral tradition, we are told, was sufficient—indeed, somehow superior—to the fragile written word. The same human mouth that forgets names, embellishes anecdotes, and rewrites personal history in its own favor was apparently, in this one case, operating under a miraculous quality-control system.

This is special pleading of the laziest sort. When anthropologists study oral cultures, they do not marvel at their precision; they study their fluidity. Stories evolve to suit the needs of the moment. Details are sharpened or softened. Heroes grow taller. Enemies grow crueler. Moral lessons are retrofitted to current anxieties. Oral tradition is not a photocopier—it is a living organism, mutating as it survives.

To insist that biblical stories somehow resisted this process is to argue that human beings behaved like human beings in every context except this one. That gossip distorted village news, legends distorted local history, and myths distorted cosmology—but when it came to Yahweh’s preferences about shellfish and slavery, the human mind suddenly achieved stenographic perfection.

The game of Telephone does not fail because children are stupid. It fails because humans are human. Memory is reconstructive, not archival. Each retelling is an act of interpretation. And interpretation is precisely what theologians later insist never happened.

Even once writing enters the picture, the problem does not evaporate—it multiplies. The Bible was not written by a single author, at a single time, in a single language. It is a stitched-together anthology spanning centuries, cultures, and political regimes. Hebrew texts were translated into Greek, then Latin, then into countless vernacular languages, each translation carrying its own assumptions, idioms, and theological agendas. Words without direct equivalents were approximated. Metaphors hardened into doctrine. Poetic flourishes became legal pronouncements.

Consider how often modern Christians argue about what a single verse “really means.” Now imagine that dispute stretched across two thousand years, filtered through scribes who believed they were preserving divine truth while quietly correcting what they thought were errors. We know this happened because we possess manuscripts that disagree with one another. Verses appear in later copies that do not exist in earlier ones. Stories materialize out of thin air, such as the famous tale of the adulterous woman—beloved, quotable, and almost certainly a late addition.

A perfect word of God would not require footnotes explaining which parts are probably authentic.

Then there are the contradictions, which believers alternately ignore, rationalize, or perform acrobatics to reconcile. Creation happens twice in Genesis, in two incompatible orders. Judas both returns the silver and hangs himself—and also buys a field and falls headlong, bursting open. God commands mercy in one breath and genocide in the next. Kings is contradicted by Chronicles. The Gospels cannot agree on who visited the tomb, when they arrived, or what they found there.

These are not trivial discrepancies. They are the textual equivalent of the Telephone message turning from “meet me at the playground” into “burn down the school.” The attempt to harmonize them usually involves inventing explanations not found in the text itself—an implicit admission that the text, left to its own devices, does not cohere.

Defenders often retreat to a familiar line: the Bible is perfect in its message, not its details. But this is an escape hatch masquerading as humility. Once details are negotiable, authority collapses. If God cannot be trusted to preserve the order of creation, the fate of Judas, or the last words of Jesus, why should we trust him on the nature of salvation, sin, or eternity? Precision suddenly matters very much when the stakes are infinite punishment.

Others argue that God worked through flawed humans, allowing their personalities and limitations to shape the text. This is an honest admission—but it detonates the claim of inerrancy. A book shaped by human limitation is, by definition, a human book. Inspired, perhaps. Meaningful, possibly. But no more immune to distortion than any other product of human culture.

The Telephone game analogy grows sharper here. If a teacher whispers a sentence to one child and allows it to be distorted by twenty others before declaring the final result “exactly what I intended,” the fault does not lie with the children. It lies with the teacher’s method. A deity capable of parting seas, halting the sun, and resurrecting the dead could presumably manage a clearer publication strategy.

Instead, we are told that ambiguity is a feature, not a bug—that confusion tests faith, that contradiction invites humility, that obscurity deepens devotion. This is a clever reversal, but an unconvincing one. No other domain treats incoherence as evidence of authority. We do not praise legal codes for contradicting themselves, nor medical textbooks for offering mutually exclusive diagnoses.

The reality is simpler and far less flattering to religion: the Bible looks exactly like what it is—a collection of human writings reflecting the fears, hopes, prejudices, and power struggles of their time. It condones slavery when slavery is normal. It subordinates women when patriarchy is unquestioned. It imagines the universe as a three-tiered structure because that is how ancient people understood the world. As knowledge expands, interpretation is forced to stretch, retreat, or quietly abandon earlier claims.

This is not how eternal truth behaves. Eternal truth does not require constant reinterpretation to survive contact with reality.

The Telephone game teaches a lesson that theology works tirelessly to suppress: transmission matters. Medium matters. Messengers matter. Once a message passes through human minds, it becomes human. To deny this is to deny the very nature of language, memory, and culture.

The real marvel is not that the Bible contains wisdom, poetry, and moral insight. It would be astonishing if it did not. Humans are capable of all three. The marvel is that so many otherwise rational adults are willing to suspend everything they know about communication, history, and psychology to preserve the illusion that this particular game of Telephone ended in divine clarity rather than predictable confusion.

In the end, the Bible does not fail because it is flawed. It fails because it is claimed to be flawless. Remove the impossible burden of perfection, and it becomes what it has always been: a fascinating, influential, deeply human document. Insist on perfection, and it collapses under the weight of its own contradictions.

The whisper was never divine. The circle was never secure. And the message, by the time it reached us, was already unmistakably human.