Feasts for Me, Silence for Thee

How Cultural Holiday Grievance Disguises Religious Monopoly

Of late, there has been a marked increase in conservative hostility toward any holiday that falls outside their approved moral perimeter. Their contention to Black History Month, Gay Pride Month, or any comparable observance is not an argument but a wheeze of indignation—the sound produced when a long-unused moral muscle is abruptly asked to function.

Why, they ask, clutching their calendars like title deeds, must these people have a whole month? It is a question posed with the injured innocence of those who mistake habit for heritage. And yet this same tribe observes a devout hush before the most baroque calendrical empire ever assembled—the liturgical sprawl of the Catholic Church, which has so densely colonized the year that scarcely a day remains unbaptized, uncensed, or unclaimed.

Let us be clear about the scale of the hypocrisy. Catholicism does not merely have a few holidays. It has seasons within seasons, feasts within feasts, solemnities, holy days of obligation, fasts, vigils, octaves, novenas, saints’ days by the score, Marian apparitions by the dozen, and regional variations to ensure that no corner of the year escapes sanctification. Christmas is not a day but an industry; Easter not a weekend but a protracted ritual drama preceded by Lent, Holy Week, and the Via Dolorosa of enforced solemnity. Add All Saints’ Day, All Souls’ Day, the Immaculate Conception, the Assumption, Corpus Christi, Pentecost, Epiphany, Ash Wednesday, Palm Sunday, and an army of canonized personalities who each demand their own commemorative slot. If memory serves—and it does—this is not an oppressed minority pleading for recognition. It is a global institution that has annexed the calendar like an empire.

Now compare this to the supposed affront of Black History Month or Pride Month. These are not theological claims about the cosmos. They do not assert divine authority, eternal truth, or supernatural sanction. They do not demand belief, obedience, or tithes. They are civic acknowledgments—temporary spotlights aimed at histories that were systematically erased, criminalized, or shoved into the footnotes. To complain that such recognition is “divisive” while genuflecting before a church that devotes entire months to penitence, virginity, martyrdom, and ritualized guilt is to confess, inadvertently, that the objection is not about excess but about power.

Indeed, the real irritation for these critics is not that there are too many celebrations, but that they are not in control of them. Catholic feast days flatter an inherited hierarchy; Pride and Black History unsettle it. One canonizes saints; the other remembers slaves, rebels, artists, victims, and survivors. One insists on submission to tradition; the other invites scrutiny of it. That is why the former is deemed “culture” and the latter “politics,” even though Catholicism has been one of the most ruthlessly political institutions in human history.

So let us dispense with the pretense. The calendar has never been neutral. It has always been a battlefield of memory. Those who sneer at Pride Month or Black History Month while swimming happily in an ocean of Catholic holidays are not defending unity or modesty. They are defending monopoly. And like all monopolists, they resent competition—not because it is loud, but because it reminds them that their dominance is neither natural nor eternal.

So let us end the charade entirely. If you dislike these newer holidays, fine—personal irritation has never required a philosophical defense. But abandon the pretense that you are oppressed because your own celebrations are vast, sweeping, and so culturally dominant they no longer register as claims at all. What you are performing is not grievance but petulance, the sulk of those who have mistaken ubiquity for innocence. And let us not insult the reader by pretending this outrage is value-neutral. When Black history or gay existence becomes “too much,” “divisive,” or “forced,” what is being voiced—carefully laundered for polite company—is the old resentment that certain people were supposed to remain invisible. Call it cultural concern if you like; it is still racism and bigotry in a blazer, indignant not because the calendar is crowded, but because it now includes faces and lives that were once excluded by design.

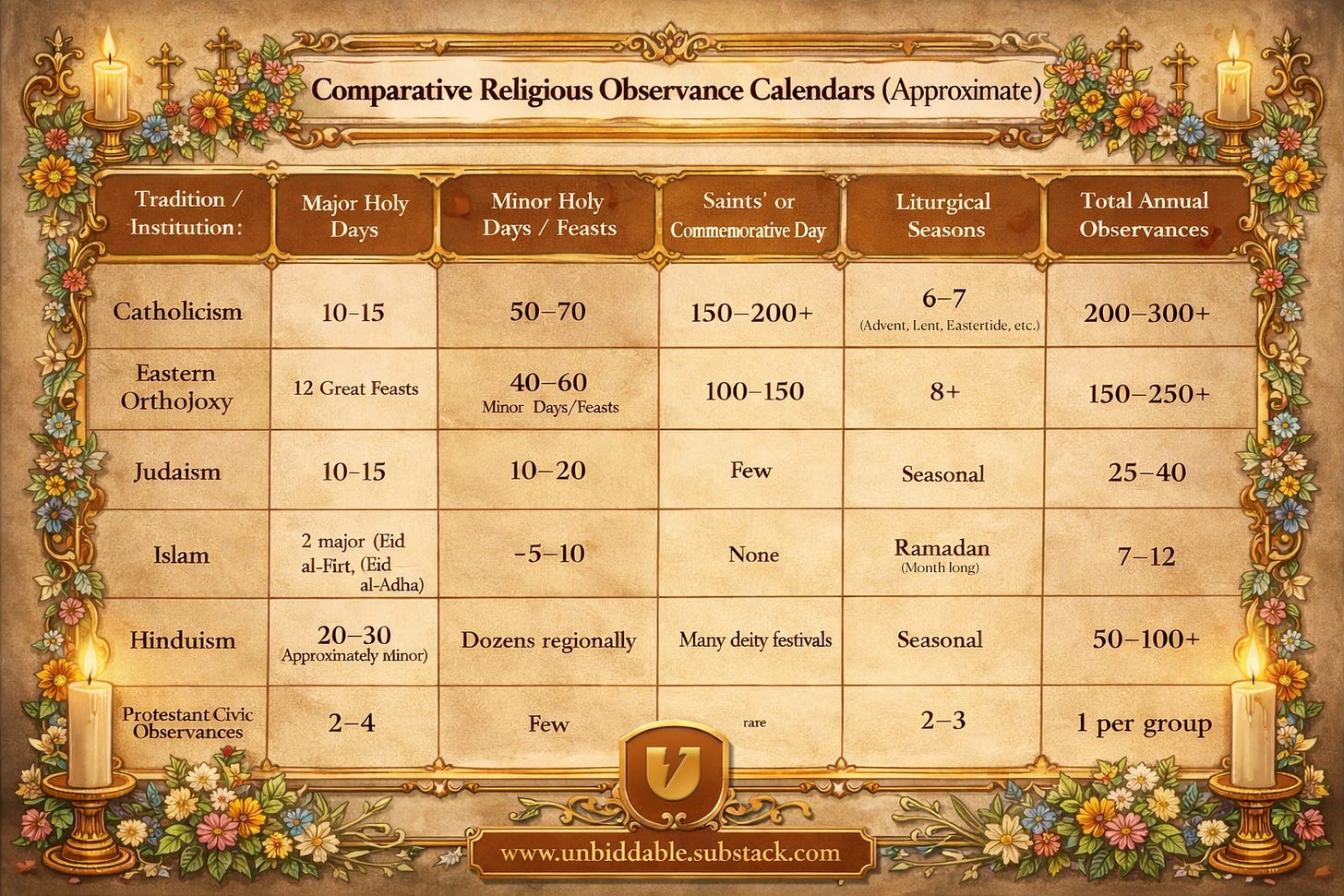

By the numbers